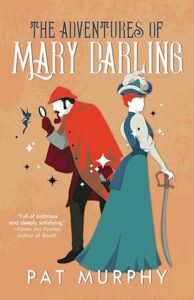

The Adventures of Mary Darling

Pat Murphy

Tachyon Publications • May 2025

One look at the cover and at the glowing advance reviews, and I knew I needed to read Pat Murphy’s latest book. The premise – that Sherlock Holmes is hired to investigate when the three children of George and Mary Darling vanish from their London home overnight – is just that irresistible. At the same time, those same reviews set off a number of my internal alarm bells – promising, as they do, a narrative sharply critical of the colonialist and Victorian sensibilities woven deep into J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan.

As it turns out, my literary Spidey-sense was right; The Adventures of Mary Darling reads – to me, at least – like a textbook example of how not to approach a literary mashup.

Let me be clear here: I have no inherent objections to either the book’s literary form or to an honest critique of Peter Pan’s problematic elements. As to the latter, Pat Murphy has done more than sufficient homework to justify that aspect of the project. But as a mashup – or crossover, the term used most often by modern fanfic writers – Murphy’s novel falls short on almost every count.

#

Broadly speaking, I have three major issues with the book. First, the title and cover art are misleading on multiple levels. Mary Darling doesn’t get nearly enough time onstage in what’s ostensibly her own book, Sherlock Holmes is at best a minor presence throughout, and far too little of the story can be accurately described as “adventure”.

Second, Murphy makes a very strange narrative choice by presenting the entire tale as a manuscript written not by her title character, but rather by Mary’s adult daughter Jane. The result is to severely distance readers from both the action (such as it is) and the characters. This is especially frustrating in the case of Sherlock Holmes, whose portrayal borders on caricature to a degree that Holmes’ fans are likely to find annoying. Watson (whom Murphy makes Mary’s uncle) comes across somewhat better – and gets one key scene that should have more impact on the story than it actually does – but is otherwise mostly a peripheral presence.

Third, the novel fails to deal adequately with the elephant in its chosen room. Murphy’s (or Jane’s) narrative acknowledges that genuine magic exists in its version of the world – but almost completely refuses to explore the consequences of that choice. Two examples stand out.

First, Peter Pan’s origin and nature are given scant and contradictory attention. On one hand, according to Jane’s narrative, he’s led three generations of children out the nursery window of the family house in London – Mary first, then Wendy and her brothers, and most recently Jane herself. Yet what we see of Peter in and around “Neverland” is a being with only a child’s memory, easily distracted or overcome either by a more promising adventure or a mother’s threat of bedtime without supper. It’s an inconsistent portrayal, and as a result Peter never emerges as a well-realized character.

Second, the story goes out of its way to avoid confronting Sherlock Holmes with the reality of magic. He’s otherwise occupied at one key moment when Dr. Watson finds himself airborne due to an accident involving fairy dust – and he’s deliberately left out of a planned “rescue” of Jane Darling from the supposed clutches of Captain Hook, likewise aided by a supply of fairy dust. This Holmes, we’re told, would disbelieve in magic even if given the chance to see it at work. That’s flatly unfair, particularly in light of the oft-quoted Holmesian axiom: “whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth” after one has eliminated the impossible.

#

Yet as badly as the novel fails on a narrative level, those early trade reviews are not entirely wrong. Ironically, the best parts of the book are those focusing on the secondary characters – sometime pirates Sam Smalls and the eventual James Hook (whose true identity is an ingenious and admirably subtle twist), Chief Laughing Bear’s family of Wild West showrunners, and Jane’s fascinating assortment of female allies. Even George Darling has his moments – and indeed, possibly the strongest character arc in the novel, not excluding Mary’s. One almost doesn’t need the authorial afterword to discern that Murphy has indeed done an excellent job of replacing J. M. Barrie’s ethnically stereotyped players with well-rounded, fascinating individuals.

At the end of the day, The Adventures of Mary Darling is a profoundly schizophrenic book. I can’t recommend it as a mashup or crossover – indeed, I suspect fans of both the original Peter Pan and the Sherlock Holmes canon will find it disappointing at best.

That said, I can and do recommend the book as what it’s been praised for: a well-crafted re-imagining of the Neverland setting with a more historically reliable and relatable eye. If Tachyon had put a full-cast illustration on the cover, titled it accurately (perhaps as The Mostly True History of Neverland by Jane Darling) and perhaps persuaded Pat Murphy to excise Sherlock Holmes from a story in which he really doesn’t belong, I would be a much happier reviewer.

Sorry to just jump in on a random post, John, but it appears the old Email I have for you (sff.net) doesn’t work, and I can’t seem to find a straight email link on this site. Maybe I’m just blind.

Please ping me back at seawasp@sgeinc.com so I can get a current contact for you! Thanks!

Ryk E. Spoor

No need to apologize (though good heavens! That SFF Net address is spectacularly ancient by now). You should have a far more current pingback now, and I appreciate your noticing the missing contact linkage. When I first built this site, WordPress was a much simpler thing than it’s since become, and my Web design skills have just barely kept pace with my ambitions….